- Home

- Matthew J. Costello

Darkborn Page 5

Darkborn Read online

Page 5

Kiff slapped his hands together.

And before he knew what had happened, he and Kiff were outside, walking through the light rain, the heavy splats matting down his hair.

While the others — the sane ones, Will thought — were on their way home.

They started out walking, but once they were across Ocean Parkway, the rain turned nasty. The occasional spritz gave way to a steady downpour that Will’s all-weather coat didn’t do much against.

His hair was sopping and the rivulets ran off his nose.

“Couldn’t we have done this tomorrow?” Will shouted through the curtain of water.

Kiff’s long red hair was, for once, all going in the same direction. Right down his forehead, nearly covering his eyes.

“I don’t know if Scott’s rehearsing tomorrow,” Kiff yelled back. “And that would just leave us Friday.” He shook his head. “It has to be today.”

Kiff reached out and tugged at Will’s sleeve. “C’mon,” he said.

Will hurried, but he pulled his cuff away. He didn’t like being touched by Kiff. Kiff was okay in the group — barely — but one-on-one, he was an unpleasant experience. Too weird.

Maybe dangerous.

They passed the Ocean Theater. It was still showing The Sound of Music . The posters showed a giant Julie Andrews surrounded by a bunch of squeaky-clean kids.

Kiff ran ahead and stood under the marquee, getting protection from the rain.

“Damn, it’s raining like hell,” Kiff said.

Will pulled his books from out of his coat, checking to see how they were doing. There were times, he thought, when a book bag might be helpful.

“Stupid-ass movie,” Kiff announced, looking at the poster.

Will nodded.

“Did you see Thunderball ?”

“Yeah,” Will said. “That was —”

“Yeah, really great. That rocket pack? When Bond blasts off? Bitchin’ movie . . .”

Will looked around. There was no sign that the downpour was letting up. Kiff lit a cigarette.

“I think we should get going,” Will said. “It’s getting late.”

“Sure, Will . . . we’ll keep going.”

And like crazy people, Will thought, they ran off, splashing through the growing puddles that gathered in the cracks and curves of the sidewalk, running all the way to Flatbush Avenue.

And on, past a grungy candy store with a giant faded Breyer’s ice cream sign, until they came to Carroll Street, lined with rows of neat brick homes.

Thick trees guarded each side of the road.

The leaves — still on the trees — sheltered them from the worst of the rain.

But now Will smelled the ground, the car oil brought to life by the sudden splash of water. The smell of garbage cans, empty but marked by years of messy spills, sitting in narrow alleyways leading back to tiny backyards.

“Okay,” Will said, feeling better now that the incessant downpour was off his face. His shirt and his sport coat were soaked near the top, a ring of dampness that was creeping its way down.

Kiff came close — the small of his breath, the unhealthy look of his skin — much too close. “It’s the sixth house down, Will. Now listen,” he said, putting a hand on Will’s shoulder.

Stop touching me, Will wanted to say.

“We walk down there, as if it’s nothing. Scott always has students coming to see him, even ones that have gone on to college. Nobody will think anything. We’ll turn down that corner, right to the back door.”

“And then — ?”

Kiff smiled. “Leave the rest to me.”

Then he turned and led Will down the block. They passed the protection of one big maple tree. Fresh drops hit Will’s face. And then on to the cover of another tree, until they came to — yes — the sixth building.

Jim Kiff took the turn into the alley as if he had done it a thousand times.

“Here we go,” he whispered to Will.

Too many James Bond movies for the Kiffer, Will thought.

The alley was dark, almost black. The stale smell was strong here, overpowering. He heard noises. A TV blasting in the house to the left. The smell of food cooking. Garlic. Onions frying.

Then they came to the backyard.

“Just walk right up to the back door,” Kiff hissed.

Will nodded.

There was a small patio in the back, and one chair. A statue, a fountain of some kind, stood surrounded by overgrown ivy. But one arm of the fat cherub statue was broken off, and the fountain listed to the left. It was speckled with black and moldy green.

Is this where old Mr. Scott comes out to do his reading? Grade his papers? Will wondered.

He turned back to the door.

“Get close,” Kiff said angrily. “Somebody might look down. Block me —”

Will leaned over, watching Kiff. He held a piece of wire.

A straightened paper clip, it looked like. Kiff kept fiddling with the lock. Then cursing. There’d be a hopeful click. And then Kiff would say shit , or damn , or anyone of the other powerful words from his special litany.

“I thought you said that you knew how to do this.”

“I do. Just shut the hell up.”

Will shook his head. It was time to bailout of this after-school activity.

A car went up Carroll Street. Slow, almost crawling, its engine just kind of lazily roaring up the block.

Just the way a cop car would do, Will thought.

Immediately he imagined the cop car. Moving slowly, maybe called by a suspicious neighbor, some old biddy who spent her day looking out her window for robbers and commies.

And then, as if to confirm his suspicion, he heard the car stop.

“Oh, shit, Kiff. There’s somebody out there.”

The car had stopped. Still Kiff fiddled with the lock, making it rattle hopefully. But nothing happened.

A window opened. Will heard it.

From a house down the road.

There, right there, Officer, Will imagined someone screaming.

Of course, the cop would shoot to kill. “I’m splitting,” he said.

But Kiff was too fast.

His hand shot out and grabbed Will’s collar. Kiff was long, lean — the definition of “wiry.” No one had guessed he was strong.

But now he was manic as hell and this thing, this crazy garbage that they were doing, obviously meant a lot to him.

“Don’t — freak —” he said slowly.

“Hey, I ‘ve —”

“If you run out there now, and there is someone there, they’ll fucking see you. Maybe it is a cop,” Kiff said with an evil smile. “He’ll nail your ass.” He took a breath. “Besides, I almost got this.”

Will nodded.

He looked back at the cherub in the garden.

Except, it wasn’t a cherub.

No, its one intact arm had something up to its mouth. And there were these two bumpy ridges on its head. Sort of like horns. And then the legs —

A different sound sputtered from the lock.

“Got it!” Kiff said.

He twisted the door handle.

And the door opened. Creaked open, louder, louder than the rain spattering, louder than the car that sat on the street, its engine quiet now, clicking, cooling.

Kiff pushed the door wide open.

He stepped in.

And when Will didn’t immediately follow —

When Will just stood there and watched —

Kiff, grinning from ear to ear, as he said, “We’re in, Will.”

And as much as he didn’t want to, Will walked inside the basement apartment.

* * *

6

Kiff just stood there.

“What’s wrong?” Will asked.

“Nothing. It’s just —”

He heard Kiff breathing, and Will looked around. He saw they were in a tiny kitchen. There was a cereal bowl on the table, crusty with Cheerios. A coffee cup, with just a cold, filmy mouthful left. A

small white stove and refrigerator. It felt damp down here.

“What is it?” Will said.

“I thought I heard something.”

They both held their breath, and Will craned his neck, turning slowly from right to left.

Because if Kiff heard something — someone — then, boys and girls, we’re not alone, Will thought. And if we’re not alone, then we’re in deep —

Screech.

They both heard the sound, and they both jumped into the air.

Before they saw the grayish blur zip across the cracked, yellow linoleum floor.

Screee-eeek , the mouse squeaked again, suddenly stymied by a wall that offered no hiding places, and it drunkenly darted back under the refrigerator.

Kiff laughed. “Just a goddamn mouse,” he said. Then he nudged Will. “Shut the door. Everything’s cool, Willy. Just fine.”

Will gently pushed the door shut and heard it click closed with terrible finality.

“Let’s do this fast,” Will said.

Kiff nodded. “Right, sure.” And Kiff walked out of the kitchen. “C’mon,” he said.

Will followed him. They entered a dark passageway — too tiny to be called a hall — and then on into Scott’s living room.

It was black, with just thin bars of gray light sneaking into the room from the windows.

“I can’t see anything,” Will whispered.

Kiff raised his hand. The old pro. Trying to steady the newcomer.

“Just keep cool, Will. Let your eyes get used to the darkness. We can’t risk putting any lights on.”

Will heard a sound coming from the front, from the stairs leading to the apartments upstairs. Kiff shot him a look. He raised his hand again, signaling him to stay still.

They waited and listened to the steps, labored, slow steps, plodding down toward them.

The footsteps stopped just outside Scott’s door.

Will backed up.

Closer to the passageway. Closer to the kitchen.

If that door handle turns, I’m getting the hell out of here, he thought. As fast as I can.

But then he heard the creaking sound of a door being opened — the front door. And whoever it was — they were gone.

“Okay,” Kiff said. “We’re all set.”

Will looked around, marveling at the wonderful clutter of Scott’s room. There was a couch, more of a love seat. And an easy chair, a heavy, uncomfortable-looking thing with a high back. But mostly there were books.

They were everywhere . On the chairs. On the floor, scattered like crumbs from a giant’s table. Stacked against the wall, leaning against the fireplace. And, of course, on the shelves that ran all the way around the room, leaving only space for the windows.

And papers too, scattered piles, probably Will’s last paper on Moby Dick . Will could imagine the teacher sitting in this dark room, this temple of books, poring over papers while he poured himself another sherry, and — what? — railed against a fate that led him to devote his life to reading the scribblings of sophomoric sophomores.

There was, he felt, something unsettled about this room.

“Okay,” Kiff whispered, “can you see okay?”

Will nodded.

“I’ll tell you where the books are — and you can go get it, the big black book, while I keep watch.”

Will turned sharply. “What do you mean?” he hissed. “What do you mean I’ll go get it? Why the hell can’t you get it and I’ll keep watch?”

Kiff came close to him, his smell, the strangeness, all but overpowering in the tiny living room. “Because I know how to look out. Will, I’ve done this shit before and —”

“Oh, yeah. Where?”

Will figured Kiff was just arranging it so that he’d be closer to the door. And where will I be? he thought. In Scott’s back room, rummaging through his stuff. Shit . . .

“Listen,” Kiff said. “I can check the front and the back doors. I know which way Scott comes.” He paused. “I can keep my head, Will. You go get the book.”

Kiff’s washed-out blue eyes glowed in the gloomy room. And yeah, sure . . . Who knows? Will thought. Maybe Kiff’s right. And the sooner I get the book and do this stupid thing, the sooner we’re out of here.

“Damn. Okay. Tell me what to do.”

Kiff pointed to the small door that led off the living room.

Is there fate? Will wondered. Or is it just my dumb luck that I ended up here, doing this?

Or was it in the cards all along?

Because this morning I sure as hell wouldn’t have guessed that this is where I’d be at five o’clock.

He moved into Scott’s bedroom.

And now he felt the creepiest. It was one thing to break into someone’s house, to walk through their kitchen, their living room.

But their bedroom?

God, he could even smell Scott, the heavy cloistered smell of sheets that needed changing. A wineglass sitting on the end table, probably lined with a dry, reddish crust. There were no windows in this room. No light. Just the pitiful glow . from the living room.

Kiff had said he couldn’t turn on any lights.

Which means that I won’t see shit, Will observed.

Everything was marked with shades of blackness.

It felt like a tomb.

Will rubbed his cheek. He looked around for the closet.

He heard something moving. But this time he didn’t jump.

Old Scott needs a cat, a good mouser to clean up his apartment.

The mouse was there, out on the floor somewhere. Will heard the squeak.

“Okay,” Will whispered to himself. “Where’s the closet …”

He turned around.

And there it was, behind him.

As if it were waiting for him.

He almost laughed.

He went to the closet door, turned the handle, and pulled it open. The door squeaked and he stopped.

He had arranged a signal with Kiff. If Kiff saw anything, if they had to get their ass in gear and get the hell out of there, Kiff would whistle once.

But if Kiff whistled twice, it meant that something had happened, that it was already too late. Everyman for himself. Women and children overboard. Rich stockbrokers into the dinghies, and fuck the Titanic .

Will listened. But beyond the door’s noisy sound, there was nothing.

He pulled the closet door open.

And the rows of wine bottles caught the small bit of gray light. Will could barely see the bottles, black, looking like rows of battleship guns, ready to fire.

He reached out and touched the bottles. He felt the dust gather at his fingers.

And the secret compartment, boys and girl — -he thought — is right behind the bottles.

Somehow.

He let his fingers trail all around, looking for a way to move the wine cellar out of the way and expose the hidden treasure.

“Shit, Kiff,” Will said at last, hissing loudly. “I can’t see anything. And I sure as hell don’t see how to get at your secret door. Are you sure you weren’t imagining all that shit?”

He heard Kiff run back to him.

“Damn, Will. Can’t you — ?” Kiff ran his hands through the rows of bottles, feeling the edges, looking for some kind of latch or something.

Will stood back.

Time to make an exit, he thought.

“Where the hell — ?” Kiff said. And then Will heard a rattle. And the rack of bottles moved, swinging out toward him. “There,” Kiff said. “I’ve got to get back and watch. Just get the book!”

Kiff vanished.

It occurred to Will that the secret door was pretty well hidden. It wasn’t, he thought, something that you could just stumble upon.

It was as if Scott had left it open that afternoon Kiff was with him.

And forgot to shut it.

Will pulled open the wine rack a bit more. The bottles rattled against their berths. Now there was a narrow entrance into the closet, with just enou

gh room for him to squeeze in. He took a step.

Thinking: There’s got to be a light in here.

And: Fuck Kiff. Fuck him. I’m turning it on.

He felt the wall, searching for a switch. He reached over his head. There was no string. But then, as his hand flailed at the air, he felt the beaded pull chain of a ceiling light.

He turned it on.

The bulb was brilliant, blinding.

“Will,” Kiff hissed from outside. “Will, what the hell — ?”

Screw you, Will thought.

Now he looked ahead. At the shelves, at the books in front of him. He reached out and touched them.

And he knew they were the oldest things he’d ever felt. Some of the titles were so worn away that the raised letters were lost in the splintery leather bindings. A few books were encased in thick plastic, hermetically sealed against any more destruction.

It’s just his collection, Will thought. A bachelor teacher’s passion. Old books.

But then Will tilted his head and read some of the titles.

“Will! Shut the damn light off!” Kiff said.

Le Mystere des Cathedrales . . . De Occultus Philosophia . . . Gate of Remembrance.

Well, sure. enough he’s got all the classics here, Will thought. Where’s Ivanhoe . . .

He saw a book called Experiments in Time . He noticed the author’s name. T. W. Dunne.

Close to my name, he thought. Close to Dunnigan . . .

He pulled the book out.

And moving the book, pulling it from its place on the shelf, seemed to stir up the odors, the ancient smells of the books.

For a second Will didn’t think he could breathe.

The smell was feral, the way an animal might smell.

After it has been sealed up in your closet for a decade or two.

But he kept pulling out the book. He opened it.

The pages were tissue thin. One page was filled with Greek. Another with Latin. A third with what looked like hieroglyphics . . . at least, he saw the telltale oblong circles of cartouches.

He turned the page and he heard it tear, a gentle sound, the paper was so thin . . . sere. And this page was in English.

“On the Manner of Displacements,” the section was called.

He read a few words, forgetting for a moment his fear. This was amazing stuff, he thought. These books were strange, incredible.

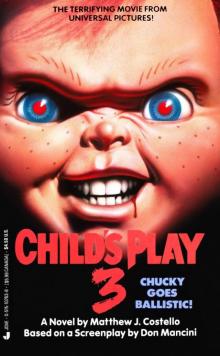

Child’s Play 2

Child’s Play 2 Darkborn

Darkborn Vacation

Vacation EXILED Wizard of Tizare

EXILED Wizard of Tizare Child’s Play 3

Child’s Play 3