- Home

- Matthew J. Costello

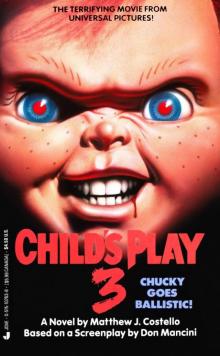

Child’s Play 3

Child’s Play 3 Read online

Andy had a little doll,

Its heart was black as coal.

And everywhere that Andy went,

It tried to steal his soul.

It followed him to school one day.

It’s haunting Andy’s life.

It makes the children scream in fear

’Cause Chucky’s got a knife.

CHILD’S PLAY 3

NO MORE FUN AND GAMES.

CHILD’S PLAY 3

A Jove Book / published by arrangement with

MCA Publishing Rights, a Division of MCA. Inc.

PRINTING HISTORY

Jove edition / September 1991

All rights reserved

Copyright © 1991 by MCA Publishing Rights,

a Division of MCA, Inc.

ISBN 0-515-10763-8

Jove Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group. 200 Madison Avenue. New York. New York 10016.

The name “JOVE” and the “J” logo are trademarks belonging to Jove Publications, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

1

The rat stuck its head out through the hole in the wall.

It sniffed the air, alert to any warning of potential danger.

After a moment’s hesitation, a moment when its long gray white whiskers twitched in the darkness, the rat scuttled out, waddling, sticking close to the wall.

There were a number of things it searched for.

It wanted water.

There were small puddles of water with a bitter taste in here. But they could still slake the animal’s thirst.

And tonight, like most nights, something else drove the rat.

Tonight it was hungry. It had chewed glue and plastic and scraps of wire. All the crumbs from ancient lunches had been found and devoured long ago.

Now, this was one hungry rat in a place devoid of anything to eat. Its hunger forced it to leave its comfortable warren of holes and rat-sized corridors.

Tonight, it waddled up to a great rubber path that ran through the building. It climbed up, smelling the machine oil, the rubber of the dormant, cracked conveyor belt.

The rat is watched up here.

They look at it.

The dolls all looked the same, bald and eyeless, staring out into the darkness. The rat didn’t look at them as it scurried past.

The rat had chewed on one of the dolls once, but the taste wasn’t good. It had swallowed the plastic. And later, back in its hole it had felt pain.

Some things can make even a rat sick.

The conveyor belt turned to the left.

Usually the rat climbed down to the stone floor at this point and made its way through the factory. But tonight it hesitated. The rat looked up and sniffed the air. The skin around its teeth, thin and pinkish, was pulled back from its teeth. It was so eager to eat, to chew something.

The rat sniffed the air. Its blackish nostrils flared while it brought its tail around, close to its body.

It sensed something.

Something different tonight.

So the rat didn’t get down. It stayed on the conveyor belt and kept waddling along the rubber highway, past the dolls who didn’t bother to look at it.

But the rat didn’t find anything, except the end of the conveyor belt.

It raised its head one more time. Fooled. By hunger, by desperation. The intrigued rat turned. Carefully—not an easy thing—it climbed off the belt, slipping, stepping on parts of the machinery. Slipping, squealing—

Until it lost its perch and tumbled to the stone floor.

It made a small squeak.

Unheard in the cavernous room.

The rat got up quickly—as if something might pounce on it. And when it did, it saw something.

A mound of melted plastic the same color as the eyeless dolls.

With something sticking out.

Hunger drove the rat closer to the mound, close to a small arm sticking out of it. The rat raised its head and sniffed at the arm imbedded in the plastic.

It chewed the arm, tasting the same taste that had made it sick once before.

The rat backed away, losing interest.

But then the rat stopped. It looked at the mound of shapeless plastic. It came closer, whiskers twitching, black nostrils flaring. Sensing something. The rat definitely smelled something. It looked left and right.

It look a few more steps, slower still.

It moved right next to the base of the mound. The rat’s whiskers touched the base. The rat moved closer, and chewed.

The rat gnawed at the mound, tasting nothing, nothing except that plastic. But—in the air—there was something . . .

It tore at the plastic, the way it used to tear at the plastic covering of the half-eaten sandwiches left by the workers. It grew excited as it chewed, squeaking.

The smell grew stronger.

The rat locked its eyes on the spot it chewed.

Then, the smell grew even stronger.

But the taste remained cold and foul.

The rat chewed, driven by hunger. Until it felt one of its fangs bite down, and then through, into the plastic.

There was a hole, a cavity.

And something bubbled up out of that hole. The rat’s tongue pushed into plastic, lapping at the liquid.

The taste was wonderful.

Once the rat had come upon a dead animal—a prize—and it chewed the animal, ripping away the skin, the fur, tasting the liquid underneath.

Now, from the plastic mound, blood began to flow. The rat chewed more, making the hole larger, and so much blood gushed out of the gnawed hole that it sprayed the rat. The rat squeaked, frenzied by the taste, the food. Chewing to get at the meat below.

But there was no meat, no skin.

And the more the rat chewed, the more the blood flowed out, at first a trickle, then a steady stream, shooting out, onto the floor.

The blood formed a stream that flowed into a drainage groove cut into the stone floor.

The rat chewed on, oblivious of the stream and oblivious of the sounds of the blood shooting out. The red river flowed down the groove, racing toward a drainage hole in the floor.

It flowed into the mouth of a pipe that directed the blood downward.

The rat didn’t hear the weird, wrenching sound of the blood flowing through the pipe. A metal throat choking on blood red bile.

And no one heard the other groaning noise the pipe made.

A crazy rattling noise as the blood flowed through the pipe, gaining speed, hurrying, hurrying . . .

The blood rushed on to the end of the broken pipe, which jutted out into space over the conveyor belt. Over one of the doll heads—eyeless, bald.

The head was at peace, its dark sockets looking out, unconcerned.

And then the stream rushed out, gushing down onto the head, spraying it with the blood. The blood hit the doll’s head and then spread down its bland face, forming a hundred tiny streams, seeping into the creases of the plastic head, gathering at the empty eye sockets, filling them.

It coursed down into the open mouth.

Then . . .

There was movement. Not just from the blood anymore, not just the spray of red, running off the glossy plastic.

The head moved.

Slowly, imperceptibly. As if a tremendous effort were involved. As if this were so hard to do, a movement almost forgotten.

The eye sockets twitched. And the mouth closed, gummy, as if tasting the blood. Then the mouth opened. It closed again, and then opened.

The doll’s eye sockets, still black, moved as if they could see.

But now the face, slowly animated, took on something more than just these dull experimental twitches.

With movement comes

memory.

And the eye sockets narrowed until they were angry slits.

The smiley, chubby-cheeked mouth turned down, forming a sneer filled with rage.

The twisted mouth opened.

Still unable to talk, to scream.

A dark cavernous pit.

Alive. Waiting.

Hungry . . .

2

Sullivan nodded to Dr. Patterson to continue. The room was dark except for the light bouncing off the movie screen. He looked at his executives watching the child psychologist.

As CEO of Play Pals, Sullivan had already decided what he was going to do—regardless of what Patterson, the corporate child psychologist, said.

Still, there were the niceties to be observed, recommendations to be considered carefully. A toy company must be responsible . . . and responsive. After all, Sullivan thought, the Play Pals Toy Company had gotten some bad press, some very bad press.

Press that nearly blew the damn company out of the water.

Although eight years had gone by since that crazy business with Andy Barclay and his Good Guy doll, Sullivan knew that he had better tread carefully.

Patterson looked at him, waiting for his attention.

“Mr. Sullivan . . .”

There was a click, and then Sullivan was looking at the slide of Andy Barclay. Not one of his favorite things to took at.

Crazy boy, crazy mother, and all that stuff about the doll—nearly destroyed his business.

Sullivan played with his pen. Eager to end this, to move on. At the sight of the famous Andy Barclay, Sullivan sensed all his executives moving around in their seats.

That boy causes fiscal discomfort, he thought.

“This—as you know—is Andy Barclay . . . eight years ago. He claimed that his Good Guy doll was possessed—”

“Rubbish,” Sullivan muttered.

“Er, possessed by Charles Lee Ray—the Lakeshore Strangler. The scandal he set off nearly destroyed Play Pals.”

Sullivan heard another click and a most unpleasant looking man replaced the cute, smiling face of Andy Barclay. It was a picture of Charles Lee Ray, dead over eight years. And still he’s messing up my company, Sullivan thought.

Will wonders never cease?

“And I have to raise this point,” Patterson said. “I have to ask if it’s worth the potential damage to the corporation to revive all of this by reissuing the Good Guy doll? Whatever the gain to our market share, any extra profits are surely outweighed by the potential damage of reminding everyone of what happened.”

There was more stirring in the seats of these well-paid executives.

Not exactly a bunch of risk takers, Sullivan thought. They would just as soon keep profits at the status quo. Don’t make waves . . .

They are forgetting just how really big the Good Guy doll was. Do they remember how well the doll sold? And the accessories, the licensing arrangements, the TV show, the money?

We do okay now, Sullivan thought. But the Good Guy doll was a damn bonanza.

Patterson shut off the projector and automatically the shades on the window went up. Brilliant sunlight poured in.

Sullivan watched his top execs squinting. Time to shed some light on this subject, Sullivan thought. He sat in his chair, rubbing his chin thoughtfully. As if saying, see . . . I’m thinking this over very carefully. This isn’t something to rush into.

Elaine Wilcox, very pretty and the best CPA in the company, turned to him. She was wonderful at masking any interest in him when anyone else was around.

A real pro . . .

She was there, ready to say what he wanted to say.

“Mr. Sullivan—” She laughed. “I’m sorry, but before this happened, didn’t the Good Guy doll outsell all of our other items two to one?”

“Three to one,” Sullivan corrected, hammering the point home.

“Exactly. And enough time has gone by to make this boy’s fantasy ancient history.”

More stirring by the other execs. But they were also wary, Sullivan guessed. No one wanted to come down on the wrong side of the argument. Let them sniff the wind. Figure out which way we are going with this particular ball.

Sullivan nodded.

Elaine looked around the table. “The factory is up and running, the market studies indicate there will be a big reaction when we reintroduce the doll—”

On cue, she turned back to Sullivan.

“We can be back in the stores with the Good Guy in two weeks. Licensing and accessories would kick in shortly after that. The bottom line, Mr. Sullivan, is that we shouldn’t let the disturbed fantasies of one small boy influence corporate policy.”

More stirring. Fannies wiggling around in the seats. No question about the direction the wind is blowing now, is there, boys?

Except Dr. Miles Patterson still has something more to say.

“What if . . .” he said, too loudly.

The fellow’s nervous. Excitable, thought Sullivan. Maybe he needs a little vacation. I’ll have to talk to him later.

“What if you make the new dolls, and—and they affect some other little boy the same way. It would be worse than another public relations disaster, much worse. This time it would destroy the company.”

Sullivan nodded. It was time to take the direct approach. He felt his execs looking at him. Wondering how he would answer the question.

Sullivan looked up at Patterson and smiled. He took his hands and locked them behind his head. Stretched back, relaxed. Just talking to the troops.

“You know, one of the hardest things to accept about this business is that it is—” Sullivan paused “—a business. And in any business, whether you’re selling toys, cars, or nuclear weapons, the bottom line is the bottom line. We exist to make a profit for our stockholders. They trust us to do that. And to do that, we have to sell to our consumers.”

Sullivan sniffed the air. Time to wrap this up. Especially since the decision was a foregone conclusion. He was merely observing the niceties.

“And our consumers are children. And children want the Good Guy doll. Damn, they deserve the Good Guy doll. It’s a good toy, a fun toy. And no whacked-out kid should spoil it for all the rest of the children.”

“But—” Patterson started to say.

Sullivan stood up.

“Now, Miles, I understand your concern. I appreciate the thought that you’ve given this matter. But I’ve made up my mind—and I think that we’re all in agreement . . .”

A brief pause while he scanned the quiet table.

“We’re moving ahead with the Good Guy doll.”

Patterson shrunk back.

Sullivan turned to the table of executives. “Thank you, everyone, for coming. And let’s have a great year.”

The executives stood up, eager to hustle back to their own offices, ready to do their part to make the Good Guy bigger than ever.

And it will be, thought Sullivan.

No question about it.

But then Patterson came up to him. Obviously a man who can’t feel which way the wind is blowing.

“Mr. Sullivan, if there’s nothing I can say to convince you that—”

“There isn’t.”

“Then I must go on record with my position. I’m totally against this.”

Sullivan smiled. The executives watched him.

Scratch the vacation. In fact, he thought, scratch Patterson. Who said we need a child psychologist on staff? Certainly not one as opinionated and wrongheaded as Patterson. Maybe he will enjoy unemployment.

“Don’t worry, Miles. Your position is crystal clear. You can be sure I won’t forget.”

Patterson’s mouth opened.

Hello. Good morning. Wake up and smell the coffee.

Finally Patterson got the message. He backed up, to his slides, his notes.

By lunchtime tomorrow he would be history, Sullivan thought. The CEO felt someone watching him from the table.

Ira Petzoid, his personal assistant. Now, here was

a man who knows what makes a business run. Petzoid waited until Patterson slunk out of the office. He did nothing to hide his grin.

Patterson shut the door behind him.

Petzoid jumped up, grinning. The other executives beamed.

“Mr. Sullivan, we’ve arranged a little surprise for you.”

Sullivan looked at the man, so eager to please, so adept at his toadying that he was truly a man born to his role.

“And what might that be?”

Petzoid put up his hand, grinned, and then bent down awkwardly, reaching under the giant conference table.

“Ah, here we are. The guys at the factory sent this over. We all wanted you to have it.”

Sullivan saw the box first. The familiar splash of red and yellow. The giant bubble letters. The box, almost identical to the original.

“Fresh off the assembly line, Mr. Sullivan.”

Petzoid handed the box to Sullivan. And when Sullivan took it everyone applauded. Sullivan looked at the doll, which was identical to the original Good Guy. In fact, thousands of old parts were ready to be used, covered with a fresh coating of plastic skin. The molds in the factory were all set.

“Why, thank you,” Sullivan said, looking around. “Thank you very much.”

Petzoid grinned and nodded, so pleased with his little coup.

“The first Good Guy of the nineties!” Petzoid said.

And the executives applauded even louder.

3

Inside the box, the doll moved his eyes—just a bit. A fraction of an inch, a micromillimeter. Just to see the men clapping. The fancy office, the great desk.

Thinking: It’s so hard.

Yes, to stay here, inside this box, looking out.

So very difficult.

How long has it been? How long was I nowhere, nothing? How long was my consciousness buried under that plastic? How much time?

He felt joy now.

Why, I’ve been reborn. I’m back from the damn grave. I’m new, fresh—better than ever.

And I can do what I have to.

He felt himself, then, being tossed through the air, landing on the table, looking up at the zillion tiny dots on the ceiling.

How long has it been? Charles Lee Ray wondered. Mighty Damballa, tell me. How long?

Child’s Play 2

Child’s Play 2 Darkborn

Darkborn Vacation

Vacation EXILED Wizard of Tizare

EXILED Wizard of Tizare Child’s Play 3

Child’s Play 3