- Home

- Matthew J. Costello

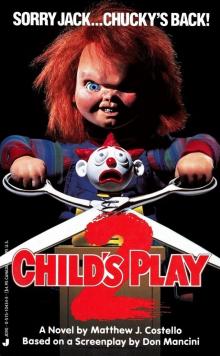

Child’s Play 2

Child’s Play 2 Read online

Once there was a doll named Chucky who did naughty, wicked things. Like murder.

But Andy and his mother killed Chucky. Killed the madman whose deranged spirit possessed the doll. Killed him once and for all.

That’s what they think.

CHILD’S PLAY 2

Andy’s in a foster home now. His mother is undergoing psychiatric treatment. And Chucky . . . ?

The toy makers decided there was nothing wrong with the doll. So they rebuilt him. Now Andy has more reason than ever to fear for his life . . .

Chucky’s back—and he wants Andy’s soul.

CHILD’S PLAY 2

A Jove Book / published by arrangement with

MCA Publishing Rights, a Division of MCA. Inc.

PRINTING HISTORY

Jove edition / November 1990

All rights reserved

Copyright © 1990 by MCA Publishing Rights,

a Division of MCA, Inc.

ISBN 0-515-10434-5

Jove Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group. 200 Madison Avenue. New York. New York 10016.

The name “JOVE” and the “J” logo are trademarks belonging to Jove Publications, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

1

He looked down.

Into a vast, bottomless cavern, its twin walls filled with jagged points and razor-sharp edges. It seemed to go on forever, into an abyssal blackness.

Something monstrous was right there, right next to the cavern, hovering, shimmering. It caught the light.

And it reflected the light right back at him, right up to his optivisors, magnifying lenses that he wore, which looked like the most high tech prescription eyeglasses ever made.

“No good,” Bob Meyer said, pulling back and then flipping the optivisors up. His eyes crossed as the room shrunk back to normal proportions. He looked over at the other technician, the other sap who had been dragged out of bed at 4 A.M. to work on this . . . this . . .

He looked at the black mess in front of him.

It was no longer recognizable, not as a doll. The head, what was left of it, was held in a vise. All of the plastic filament hair had been burned into a thick crud that stuck to the skull frame like tar.

The other technician, an old-timer who had been with Play Pals Toys from the beginning, licked his lips and gestured at the thing with his hands. Hal Turner had helped create it. Not that he ever got a penny from the thousands, the millions, that were sold. But he had been there from the beginning, working on the design, making the primitive animatronics work.

Now, he acted like an embarrassed father who sees that his kid has gone wrong. A little breaking and entering, a little first-degree murder . . . Where did I go wrong?

“I’ll move the light,” Turner said, coughing as if nervous at how thin his voice sounded in the large lab.

Meyer nodded while Turner positioned the light behind the doll’s deformed head.

Now the head was outlined, and Meyer could almost make out the sickeningly recognizable shape, the cute, adorable face that America’s rug-rats loved.

The Good Guy doll.

Except this one had been through hell.

No . . . something worse than that. This one had done something bad. Or so the papers said.

“That’s good,” Meyer said, watching the light fall into position.

He flipped down the optivisor, and the lab blurred into mammoth proportions. “Okay,” he said, “now let’s take another look.”

Meyer leaned close to the skull. And the closer he came to the head, the more he smelled the foul stench of burned plastic. He peered at the one eye left in the head, looking into the crack. If there was something wrong with the doll’s photoelectric and audio sensors, it would show up here. The eyes actually acted as sound-and-movement sensors. The doll could detect where a sound was coming from, turn its head, and say, “Hidey-ho! Wanna play?”

And that’s about all it was supposed to do, that and utter a few more reassuring things like, “I like to be hugged.”

But this one didn’t just like to be hugged. This doll—Chucky—had done a whole lot more.

Meyer brought the scalpel into the crack. He saw the now-gigantic blade slide into the cleft of the valley, testing the ragged walls. He paused just a bit and—

“Do you see anything, Bob?” Turner asked. “Are the sensors still intact?”

Meyer sensed the other technician behind him, standing very still. But he was standing well back, still disowning his offspring.

Meyer pushed against one wall with the blade, trying to nudge it open a bit more. The eye seemed intact. He moved the blade to the other side, pushing gently, then with a bit more force.

Except for the crack, the eye seemed fine, nothing wrong with it at all.

“No,” Meyer said. “Everything’s—”

He was still looking at the giant eye, the giant blade. He nodded to Turner. They’d be able to get the circuits up and running, maybe see what had happened—

The blade moved. Something gave way . . .

The eye moved. It seemed to slide out of the black, crusty hole, pop out. Into the air.

Without thinking, Meyer recoiled. It had to be flying right at him. He tried looking for the eye, but everything was, of course, oversized, a great smeary, crystalline blur.

“Where is it?” he muttered. “What the hell happened to it?”

He heard it fall.

“Damn!” he said.

“I—I guess it was loose,” Turner said, annoyingly repeating the obvious.

“Right,” Meyer agreed.

He flipped up his visor. The twin hemispheres of the lone eye were at his feet, useless now, completely disconnected from the CPU of the Good Guy doll’s computer chips. They’d have to put in new eyes now, rebuild the entire thing, just to see if they could figure out what in the world—

He looked up at Chucky’s head.

God, it looked even more like a skull now. Most of its tough plastic teeth were gone, and now it had two black sockets where its bright blue eyes used to be.

And it was staring right at Meyer.

Funny thing, he thought, taking a breath. He could still see the puffy pouches of the Good Guy doll’s cheeks, as if it were still a happy little Good Guy, sure, smiling right at him, just waiting for its next adventure . . .

“Okay,” he said to Turner. “Let’s start rebuilding the sucker.”

It hadn’t been easy getting the doll from the DA’s office.

No, Sullivan thought, as he looked out the window of his limo. His Lincoln rumbled across the Wacker Street Bridge. A hint of color touched the sky. A bit of purple, a pale orange. He reached out and took another sip of his coffee.

Tom Sullivan wasn’t used to such early hours. Not anymore, not since the small company that he had begun with just one toy concept had turned into an entire industry. It wasn’t just the Good Guy doll and accessories anymore. There was the weekly Good Guy television show, ever-steady in the afternoon ratings no matter in which time slot some local station stuck it. And there was the movie, finally with a halfway decent script—a live-action Good Guy film with some major bucks behind it. The income from the Good Guy clothes alone was more than what Sullivan had made in his first five years. This Good Guy was the horn of plenty. There seemed to be no end, no limit.

Until the incident.

That’s how he referred to it. The incident. The police had their own theory, one that the press had jumped on with their usual blood lust for a hot story. The tabloids went crazy—the strange little boy and his killer doll!

Maybe someone in the Play Pals factory had tampered with one of the dolls, altered its circuits so that it said, “Hi, I’m Chucky, the L

akeside Strangler!”

And maybe it was programmed to do other, more malevolent tricks.

But the police wouldn’t let Sullivan have the doll—what was left of it anyway: a chunk of the torso, all burned out, and the head.

Not until last night.

Finally his lawyers were able to obtain a court order forcing the DA to hand the remains over, now that the principals were all accounted for: the mother, the kid. The DA’s office was curious about the doll too.

The facts of the matter were simple enough: Nobody knew what had happened. Not a clue.

In the meantime, the sales of Good Guy dolls, Good Guy toys, and Good Guys clothes quickly declined. Some stations even dropped “The Good Guy Show”! It was bad, and it looked as if it could get worse.

Unless, Sullivan thought, we find out what did happen to that damn doll . . .

He took another sip of coffee. It was cold, almost oily on his lips. He spat it back into the cup. His limo hit a bump, and some of the coffee sloshed over onto the black carpet, nearly dotting his shoes.

He didn’t want to get involved. At first, he thought he would just let his technicians work on the doll, let them play detective.

But then his lawyer pointed out one key fact. “It’s your company, Tom. And no matter what went wrong, it’s your neck on the chopping block.”

He rubbed his cheek, feeling the rubbery texture of his skin. I need my morning workout, he thought. My bowl of oat bran. A massage. A steam bath.

Instead, the limo took a deserted corner, turning away from the pale blue glow that was blooming in the east.

Sullivan looked out the window. Right at the Play Pals building, right at the oversized Good Guy who waved at a sleeping Chicago from atop the building. The Good Guy’s giant arm went up and down, and his eyes blinked. His freckled cheeks looked even rosier highlighted by the first light of dawn.

Sullivan looked up at the giant doll as they passed by the building and thought, It looks like a monster. A giant creature out of a Japanese horror film. Attack of the Killer Good Guy.

The limo stopped.

His door was popped open.

And his smile faded.

The scalpel hit metal . . . probably a screw, Meyer thought. The head armature itself was made of a fire-resistant plastic.

Meyer scraped away the burnt covering, then leaned over to his silver tool tray and wiped his blade clean, leaving a thick tarlike paste behind. This was more like sculpting than cleaning, because the goo was solid and he had to chisel through it.

Finally he leaned back and looked at the head.

“What do you think?” he said to Turner.

The older technician stood a bit closer, less frightened now that the burnt black covering was breaking off.

“You—you’ve got most of it.”

“Okay, well then—how about some chompers for the boy . . .” Meyer stuck his plastic-covered fingers into the doll’s open mouth.

He sensed Turner tightening up, thinking, Meyer guessed, better you than me, pal. Meyer watched his fingers disappear into Chucky’s black maw as he dug around for the molars. He felt them—all wobbly and lose—and quickly popped them out. The doll only had two of its front teeth. And they both sprung free after a bit of tugging.

He took a new set of teeth from the tray, two plastic semicircles of uppers and lowers. Meyer had to force them into the sockets—something had obviously gotten a bit twisted in there.

“Hand me the epoxy . . . ,” he said to Turner.

He saw Turner’s hand shake as he handed him the small glue gun. Meyer filled the holes and gaps he felt with a thin line of the fastener.

“We should hurry . . . ,” Turner said.

Meyer looked up at the clock. 5:40 A.M. Disgustingly early in the morning. They had only twenty minutes left. Twenty minutes before the boss arrived.

“Okay, okay,” Meyer said. “I’m almost done here.”

Meyer picked up the latex mold that fit flush to the doll’s head. He held it in place and then grabbed a staple gun. He pressed the trigger, shooting the staples into the edge of the mold. The doll had skin again.

He picked up a clear piece of acetate covered with orange dots. He pressed it against the doll’s new face and presto! It had freckles.

“Hey, kid,” Meyer said to the doll. “You’re not looking too bad.”

But the doll still had a smudgy black cranium. Turner handed Meyer the hair.

“Nice mop. God, where did they get that color red?” Meyer positioned the hair on the doll’s head. It didn’t seem to land right, first a bit too far forward, then a bit back, always exposing some of the burned shell.

Finally Meyer just shrugged and brought the staple gun up again to fasten the scalp down. It didn’t have to look perfect . . .

“Okay, Hal . . . he’s all yours . . .”

Meyer backed away as Turner carried a Good Guy torso over to the head. The overalls were a brilliant blue, and the colorful striped shirt shone in the light.

Turner seemed to take forever fitting the head to the body. Then he stepped back, admiring his work. He looked around and picked up the arms. He started putting one in the wrong socket, getting the hand backward.

“Oh,” he said to himself.

What’s the guy so shook up about? Meyer wondered. Is he worried because he helped create the Good Guy? Is he afraid he’ll lose his pension?

Turner finally got the arms right. Then he put the legs on. One of the doll’s red sneakers slid off.

“I’ll get it,” Meyer said.

He bent down to the floor and picked it up. The sneaker’s sole had pictures imprinted on it of objects important in the Good Guy universe: a tepee, a horse, an airplane, a hammer.

A hammer . . .

The baby-sitter, the woman’s friend, had been killed by a Good Guy hammer. Right through the skull . . . and then she fell out the window. Seven stories down.

The kid said that Chucky must have done it.

Nobody believed that . . . But that just left the kid as the numero uno suspect.

Meyer stood up and put the sneaker on.

And then he looked up.

The doll was staring blankly right at him, almost complete, almost intact, almost new . . .

“Now for some new baby blues . . .”

He reached out and took the two eyes off the tray. He felt the back of each eye for the small nine-pin connectors that plugged right into the head’s computer board, which, unless he was crazy, had to be malfunctioning. But their orders were to try and get the doll up and running—if it was possible.

He fit the eyes into an attachment on the laboratory drill that hung suspended over the doll. The drill would lower the eyes into the skull and plug them in.

He popped each eye into the attachment. Then—hesitating for one grisly moment—he stuck a finger into each eye socket, making sure the black holes were clear. He had his fingers stuck in the holes when he heard a sound.

After a moment he realized it was the sound of the elevator arriving, just down the hall.

Meyer looked back at the doll, complete except for the eyes, and said, “Hello, Chucky! It’s show time . . .”

“Good morning, Mr. Sullivan.”

Sullivan nodded. He saw Mattson, his Operations VP, standing beside the chauffeur, looking cold and uncomfortable. Good, Sullivan thought. At least that makes me feel better. Then he saw the briefcase dangling from Mattson’s hand.

“I’ve got a board meeting in an hour . . . I hope you have some good news . . . ,” Sullivan said. He walked past the chauffeur, heading straight into the building.

Mattson hurried to walk alongside Sullivan. “Yes, Mr. Sullivan . . . I mean, there’s some good news and . . .” Mattson ran ahead, turning to Sullivan in midstammer. He grabbed the door that led into the Research and Development Building. Sullivan had to break his pace while Mattson fumbled opening it.

“Yes, go on,” Sullivan said, “Your news . . . ?” He walked inside a

nd immediately smelled the plastic, a sweet, dizzying, all-pervasive odor. Sullivan didn’t like coming here anymore.

Mattson popped open his briefcase, propping it against his body as he walked. He took out some manila folders.

“There are the sales records, Mr. Sullivan. They seem to have bottomed out. Whatever . . . er . . . damage we’re going to take, we’ve taken.”

“And the police?”

“They’ve denied the whole story, everything the boy and the mother said. They’re willing to wait until we’re done, until we’ve come up with some answer.”

Mattson handed Sullivan the first folder—a sales graph. Then he handed him two more. “The mother—she’s been placed under court-ordered psychiatric observation. And I think the cops involved have been put on paid leave. Nobody wants the story to get out . . . at least not the way she told it.”

Sullivan nodded. They walked to the elevator at the end of the corridor. Sullivan beat an embarrassed Mattson to the button. Then he flipped open the folder labeled Barclay, Karen. He looked at her photo. She was a pretty woman, a sales clerk who sold jewelry. There was nothing in the photo to indicate that she was an unbalanced woman. Mattson handed him another photo.

Barclay, Andy.

“The boy is still at the Glencoe Children’s Crisis Center. He’s going to be placed with foster parents . . . until his mother is out. He’ll also get regular counseling, therapy . . .” Mattson paused and Sullivan shot him a glance. “But he’s been sticking to his story, says the doll was real, that it was alive, that it . . .”

The elevator arrived with a cheerful ding and Sullivan hurried in. After all, he didn’t want to hear any of that malarkey.

Not a bit of it . . .

2

Mattson pushed open the door for him while Sullivan glanced up at the sign that said Research and Development.

How long has it been since I’ve been here, he thought. Not since the early days . . . And, as he walked into the observation room of the lab, he saw that a lot of things had changed.

He faced an enormous plate-glass window with a panoramic view of the lab, which was enormous. Black boxes lined one wall, and various drills and hoists were suspended from the ceiling—everything needed to design and test the modern toy.

Child’s Play 2

Child’s Play 2 Darkborn

Darkborn Vacation

Vacation EXILED Wizard of Tizare

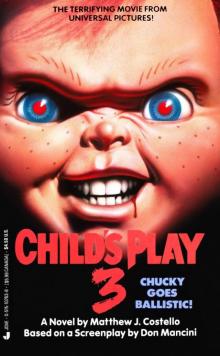

EXILED Wizard of Tizare Child’s Play 3

Child’s Play 3