- Home

- Matthew J. Costello

Darkborn

Darkborn Read online

Darkborn

by

Matthew J. Costello

A revised edition with a new introduction published by

Necon Ebooks

This Edition Copyright 2010 Matthew J. Costello

Introduction Copyright 2010 Rick Hautala

* * *

DEDICATION:

To Rick Hautala,

Friend, writer, time traveler

* * *

Table of Contents

1

St. Jerry’s, 1965

2

3

4

5

6

7

11:35

8

Friday

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

12:08

19

A Midbook Reverie by Rick Hautala

Kiff

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

1 A.M.

32

Joshua James

33

34

35

36

37

38

1:15

39

Manhattan Beach

40

41

42

43

Epilogue

* * *

1

Will Dunnigan woke up.

And for one terrible moment he didn’t remember ever falling asleep, didn’t know where he was, didn’t even know what the hell he could be doing here, inside this car —

It wasn’t his car.

He knew that.

Breathing the stale air, hearing the sounds outside. Horns honking through the streets, faint voices from somewhere behind him.

His own breathing.

Then — not a gift, but more like a curse — he remembered where he was.

And why he was here.

He looked at the dashboard clock.

Will watched the clock. He licked his lips.

It’s not too late, he thought. I’m not late. In fact, he thought with a weird satisfaction, I’m early. Even though I fell asleep, I’m early. Always did like being punctual.

I have lots of time now.

11:03.

Will pushed his thinning, sandy-blond hair off his forehead. And he looked out the windshield, all steamed up by his breath. He rubbed his sweater sleeve through the dewy window, clearing a smeary arc.

So now he got a good look at the freak show. Right outside.

Right there, ladies and gentlemen.

And while he watched, he leaned over and checked that his door was locked, that all the car doors were locked, before he let himself just stare outside, safely sitting in the dark car.

He heard his breathing.

I’m breathing much too heavily, Will thought.

But then . . . who wouldn’t?

Will didn’t want to take his Toyota tonight. It wouldn’t be fair, he reasoned. No, not to leave Becca with both a missing car and a missing husband.

Not fair at all.

The car got the shopping done. It got the kids to their ballet classes, their piano lessons, soccer practice . . . the too-busy routine of suburbia, the stuff that constituted the good life.

All of it now light-years away, galaxies removed from here . . . and now.

Funny. What time can do.

Time and circumstances.

Will cleared another smear on the part of the windshield facing the passenger seat. Now he could see the street sign. He was parked just a bit back from the corner of 28th Street and Madison.

Nice neighborhood to live in, he thought. Real nice.

If you like crack dealers, and hookers, and homeless wraiths who shambled around as if they might discorporate in the blinking of an eye.

And then there were the horny cruisers who trolled these streets-so busy during the day and now abandoned to these new-age horrors-searching for a moderately cheap thrill. Some of them had kiddie seats in the back of their station wagons . . . model fathers.

Will saw a tall black girl standing across Madison Avenue, right in front of the bank.

It was as if she had materialized. She wore gigantic spike heels that raised her to true Amazonian heights. A tight leather skirt. Straight jet-black hair that had to be a wig. Her short half-jacket exposed a flat-as-a-board midriff that gobbled the silky white color of the tungsten streetlamps.

She saw him.

Sitting in the car.

Dirty little man, she probably thought.

Will looked away, but not quick enough.

The hooker crossed the street, moving toward him like-a lioness, flashing brilliant white teeth as if she were saying:

I could eat you right up, babe. In one quick gulp. No problem.

She hurried across, dodging a mad cab that flew right past her.

She walked up to the car, and then she paused. She looked up and down, checking for signs of John Law. Solicitation was still — officially — a crime in this city. It was still on the books. Officially . But after midnight, the blocks around here became a regular Satyricon , filled with sexual wonders and nightmares that had to be seen to be believed.

And Will guessed that those who sampled such pleasures weren’t too troubled by AIDS. Life’s too short . . .

The hooker stood right by his window. She smiled at him. Big, open —

The better to —

She tapped the window, signaling that he should roll it down and get the transaction going.

Will smiled back. _

An ineffectual grin that he hoped said, “No, I’m not shopping tonight . . .”

He hoped she wouldn’t assume that he didn’t like her.

That she wasn’t to his taste. He didn’t want to get her mad.

She shouted through the glass.

“Hey, baby . . . wanna go out?”

A euphemism. Will shook his head, and smiled some more.

But the giantess leaned close to the window. She stuck out a long, dark tongue and made a licking motion with it. “C’mon, baby!” she said. “You’ll love it.”

Will couldn’t hold the smile on his face any longer. He shook his head and turned away.

The woman cursed at him. A fusillade of fuck-yous, then, storming away, teetering on her giant heels, she turned and delivered what she must have thought was the ultimate blow to some creep from the hinterlands of Westchester or Suffolk.

“Fuckin’ faggot!”

And when she turned and said that — with cars, and then a growling bus gliding past their intimate street scene — he saw something. Just below her chin. Bobbing up and down as she yelled at him.

An Adam’s apple.

A TV hooker, he thought. Or a pre-op transsexual, working her way through the college of hard knocks, saving her nickels and dimes for that big operation.

If the crack man doesn’t get it all.

He does have sticky fingers.

Will looked at his hands.

Gripping the steering wheel.

Holding on as if it were a life raft.

He shook his head, disgusted with himself.

What the hell am I doing? he wondered. If this little encounter rattles me, then, shit, what’s going to happen later?

What’s going to happen when I have to go out there?

It was cold, but he felt icy beads of sweat on his forehead.

And you are going out there, he told himself.

; You are.

And not just for that he/she hooker, not just for all the others, wandering around, blundering their way through the night, not knowing what the hell they were up against.

They don’t read papers.

No, not just for them. You know that.

It was more than that. Much more.

He let go of the steering-wheel heel.

Look, Ma, no hands.

He felt as if he might float away, that the roof of the rented Toyota would explode upward, and he’d be sucked out. Sorry, sir, this car wasn’t meant to cruise at ten thousand feet.

Again, he heard his breathing. He thought: I sound like a three-pack-a-day nicotine fiend, battling emphysema pneumonia.

Or maybe, maybe it’s just a goddamn death rattle.

He turned and looked in the backseat.

Will saw the black leather attaché . . . more like an old school bag. He leaned over his seat and pulled it to the front, onto the passenger seat. He stopped and checked the rearview mirror.

A few headlights, but nothing that looked like the outline of a police car.

Will opened the bag.

The bag’s buckle felt cold, and when it snapped open, a musty, ripe smell erupted from inside the bag. Old leather and a sweet food smell, a bit of apple, perhaps a sandwich . . . drying things, all leaving their imprint inside the bag.

He pulled out the book. It was on top.

Black. The leather was cracked. It felt heavy, leaden in his hands.

God, I’m so tired, he thought. If I could just get to a bed somewhere, just eight hours. Eight hours of real sleep. That’s all —

And then he felt for the other things.

The jar, clear, shining, catching the light. He wedged it into the crack of the seat. Then the yellow pad, filled with page after page of notes, suggestions.

And then — hard, metallic, and a bit more reassuring — the gun.

I’ve never fired a gun, he thought as he quickly took it out of the bag and slid it onto his lap. He let his hand stay closed around the handle. His finger touched the trigger — ever so gently. Just testing that it would, in fact, give when he pulled back.

It was, he was told, a .45-caliber pistol. The beefy sporting-goods guy who sold it to him said that it would punch a good-sized hole in someone.

“About the size of a baseball.” The man grinned. “Great for target shooting,” he added when Will looked up at him.

Will bought a box of bullets. There were twenty, maybe thirty shells. More than enough.

If they do anything at all.

But he felt better having the gun.

Then, at the bottom, he felt the last thing, wrapped in black velvet. His fingers traced the outline, feeling the bumps and curves, and the way the velvet caught at the calluses on his hands, the way it caught at his chewed fingernails.

He didn’t pull that out.

No. He smiled to himself. That would dispel some of its mystery, its power. Now, wouldn’t it?

If it has any power.

And if it doesn’t?

I’ll die. And worse.

I’ll die painfully. It might last a few seconds, but it would seem as though it lasted forever. A lifetime of pain, terrible, horrible agony.

Forget the Inquisition. Forget the good old Spanish priests who really knew how to party. The fun guys who’d take a pregnant woman and stretch her on a spike-filled rack and then hoist her up by her ankles and let her fall to the concrete.

Until she confessed her sins . . .

Forget the Salem witch-hunters who left people chained and naked while vermin came and chowed down on their extremities.

That’s nothing compared to what will happen to me, Will thought.

And he pulled back his hand from black velvet.

He looked left. The driver’s window was fogged up. He wiped at it.

The store across the street had closed.

A few minutes ago — or was it an hour, two hours? — it had been open. He didn’t remember.

It was a fruit and vegetable store. He remembered brilliant floodlights outside the store, hung from a green awning. They illuminated the bright, inviting display of sparkling lettuce, and blood red tomatoes, and plump squash, and grapes of every kind. Oriental men in white coats bustled about, checking the produce, weighing selections for customers.

Now all the produce was gone. The store was dark. The men in their white coats were gone. The awning had been folded back into itself. Corrugated riot doors covered the windows.

I wish they were still here, Will thought.

To keep me company.

He looked back across Madison Avenue, and the black hooker was gone. Scooped up by some lucky, if unsuspecting, soul about to taste the duplicitous pleasures produced by sexual camouflage. Will saw another girl, a different professional, standing across from the bank. She was chunky, with waves of synthetic blond hair.

Probably young. Probably much too young.

Where do they come from? Will wondered. And what could possibly make them come out here, to stand here, night after night, in the cold, in the rain?

Has life gotten that nasty, that tough?

A white Cadillac, with incongruous pink pinstripes, took the corner and pulled up to the girl. A tall black man in a leather coat got out. The man talked to the girl and gave her something.

Will watched, in the darkness of his car. Feeling like a spy, a voyeur. They don’t see me.

But I see them.

He watched the girl take whatever it was the man had proffered and bring it up to her nose.

She kicked her head back. And she grinned. A nice big grin visible from all the way over here.

Thanks. I needed that, her smile said.

The pimp got back into his duded-up wheels and made his whitewall tires screech as he pulled away.

Just putting another dime in the meter.

Keep his girls running.

As simple a concept as the donkey and the carrot.

Will heard a noise from behind him.

Shit, he thought. Goddammit. His hand closed on the barrel of the gun and then moved around to the handle. His heart raced, and he scolded himself.

Stupid, absolutely dumb! I should be checking the rearview mirrors, watching all around. I can’t get caught up in the street theater.

I can’t screw up, not tonight. Even if that is what I do best. I can’t screw up.

Not tonight.

He turned around just as his hand felt the gun handle.

And if it’s a cop, Will thought, what will I do then?

What if he starts looking in the car? What if he sees the gun? There were supposed to be cops all over here.

Supposed to be . . .

But it wasn’t a cop.

It was — yes — a homeless person.

When I was a kid we called them bums, he thought. Mom used to warn me. Stay away from the bums. And when I went to the city, to Manhattan, I’d spot them on the subway platforms, ghostly, rag-like creatures, one hand bent in a permanent cup shape, searching for a coin.

And Will learned to keep his eyes off them, to move away.

Sometimes there’d be a blind guy with a dog, stumbling through the subway car. Looking up at nothing, rattling along with the car. Stumbling this way and that, sometimes falling into people. Excusing himself to the embarrassed passengers in their seats. While the blind man held his tin cup at the ready. Right below his neatly lettered sign that read:

I am blind.

Please give whatever you can.

Praise God.

And then there were the cart men, the guys with no legs. Will never asked how they lost their legs. He didn’t want to know. It might be catching . . .

They were the scariest, those legless people who seemed so full of energy, waving pencils at people as they hurried by. So scary, as if they could threaten to turn you into one of them, and you’d become a cart person if you didn’t give them something, anything.

N

ow they were all called homeless.

And now there were committees and action groups, and people said it was our responsibility to do something, that it could happen to anyone.

He had been right as a boy. You could turn into one of them.

Nobody cared if a lot of them preferred the streets to the shelters, that they actually liked rustling through overflowing mesh garbage cans for discarded McDonald’s buns and stick fries. They liked living in the underworld.

And they still scared him.

Will watched this man shuffle next to the car. He was of indeterminate age. He might be twenty. He might be seventy. He had a beard that surely carried the leavings of countless grisly interactions with food and God knows what. He wore a regulation brown coat, Rapping open to the breeze, probably covering layers of clothes.

They wore all their clothes when it turned cold, layer upon layer upon layer.

It was easier than carrying them.

But this fellow also dragged a cherry-red Bloomie bag filled with his life’s treasures. The man stopped before he got to the corner. He put down the bag and then looked around, waving back and forth as if a good stiff breeze would blow him clear off his feet.

He didn’t see Will.

The man dug at his groin, pulling at what must be a bunch of zippers.

He was only feet from Will.

Who kept watching him, fascinated.

This is like bizarro television, Will thought.

The human circus.

The man finally hit pay dirt. He arched away from a pillar-like protrusion of the office building and urinated. The wind caught the steamy smoke . . .

At which point in the show, Will turned away.

Will kept looking away, giving the man time to move his act on.

Can’t blame him, Will thought. When you gotta go, you gotta go. And where the hell are you supposed to pee in the city? There are no toilets in the subway — they’re all locked up.

Though you’d have to be crazy to venture into one of those halls of horror.

In Paris, they had WCs right on the street, discreet cubicles where you could relieve yourself.

Child’s Play 2

Child’s Play 2 Darkborn

Darkborn Vacation

Vacation EXILED Wizard of Tizare

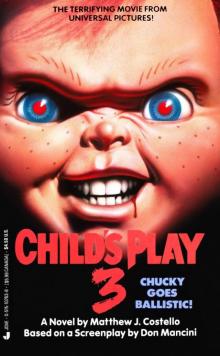

EXILED Wizard of Tizare Child’s Play 3

Child’s Play 3